viewfinder

Many in the non-profit industrial complex are pivoting to meet a newish trend. They hope to elevate the voices of people who have long borne the brunt of a racist, capitalist, and artificially-white-supremacist society. In the united states, a narrowing majority has spent generations as the only ones whose voices society uplifted. So how do you elevate others when one group has always held the spotlight? How can we elevate people who white dominant culture long destabilized? How can we finally put them into focus? It starts, and must not end, by moving the camera.

the camera itself

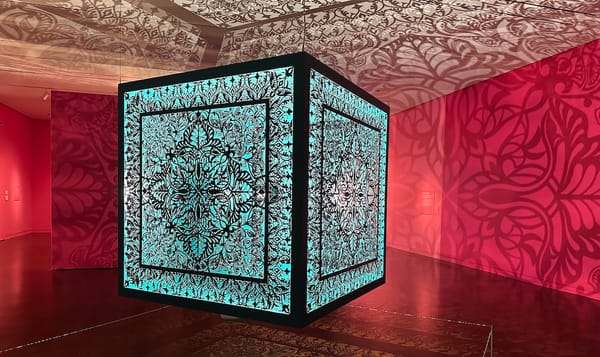

Say you’re holding a camera. It’s a standard point and shoot, any level of technology. You might twist the lens to change focus, or tap a different part of the screen to do the same thing. You’re looking through the viewfinder at two people: one close, and one far. Say, in this transparent allegory, you’ve been looking at the close person for centuries. You watch them shift and move in the light, but you rarely need to adjust your focus to see them. And the person that’s further away shifts and moves too. Sometimes they move nearer to you; sometimes they move back. Sometimes the nearer person turns around and looks at the one behind them. How can you look at them both?

the act of looking

Now you find yourself, for the first time, wanting to look at the other person. Get a real good look at them. You can’t just point your camera at this new person and see them, at least not clearly. You have to change the focus. Twisting the lens or tapping the screen brings no pain to the person nearer to you. You’re only looking at a different person, and not even forever.

What you holding the camera might not realize is the focus isn’t all that’s necessary to see the person further away. You might think all that needs changing is who the camera is pointed at. But that would ignore the racist history of film chemistry. It would ignore those who wrote the algorithms the lenses use to capture images. It ignores you, the person who is holding the camera. How long have you been holding this thing? Who held on to the camera before giving it to you? Who taught you how to use the camera, where to point it, and what was important to look at?

It also ignores the history of why that other person has always been out of focus. Why they are so far away. And when you start focusing on other people, who else might emerge from the background? Who else might you have never noticed before? Who else has always deserved to be seen?

reality bites

But for so many leaders in the public sector, they believe that all you need is to gaze towards what now matters. Those of us who have always been around are now at the center of the viewfinder more than we used to be. And suddenly the world is changing for these leaders. Suddenly, they’re or we’re called to do things in a way that’s different, for the first time ever.

But what has changed, really? People in power are still exactly where they’ve always been. We may have a seat at the table, a folding chair placed at the corner of their mahogany boardroom. What is the same? Everyone else at the table. The board that affirms their power. The others in leadership that take their cues. The donors they speak to. The audience they think about.

Some believe they can live an entire life in an artificial white supremacist society and emerge unbowed. Or in the space of a single (optional) two-hour session, these leaders will be able to do the new work we must demand. They believe they can use the same equipment and film they have always used. The techniques that feel natural to them. The discomfort that can last for sheer minutes before they insist we change the subject. And the faint awareness, almost out of frame: the only truly moral act that people now in power can take is abdication.

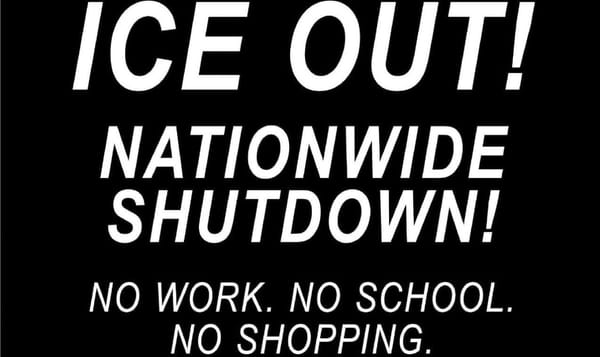

how we get free

I’ve wrestled with these concepts a lot lately. I’ve had some crystallizing conversations with a few people I’m lucky to know.

Abdication is not going to happen in my lifetime. I’ve realized that we have to do it all over. We need a complete reenvisioning. We can’t change the world from the view at their table. We have to take a step back and find a different way towards the future we know we all need.

If we do it another way, and it’s successful, they’ll steal our ideas. Take credit for them. We’ll come up with new approaches. The ideas themselves aren’t even new; what’s new is how we use them. We’ll reimagine the models we’ve lived through and make them better. This continuous adaptation is not without purpose. Our goal is to keep creating until we have something that looks unrecognizable to them.

What we’re doing is rebuilding our world. Step by step. Until all that’s left is the future we’ve made.