playing favorites 2025

we will always be here

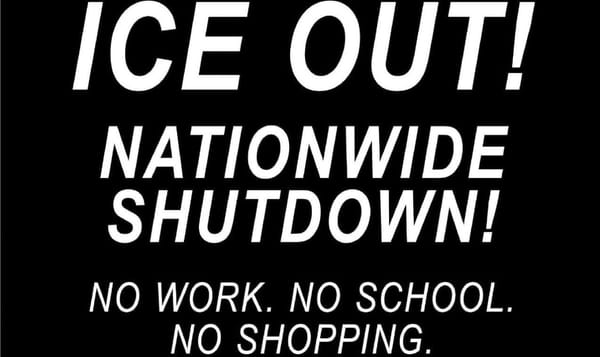

The tilt of my favorite books this year is decidedly queer. Attacks on the LGBTQIA+ community, especially our trans and intersex family, reached a fever pitch this year. I sought out these books for comfort, for escape, and as a reminder of how brilliant and beautiful we are. All of us (except for the rich white gays and transphobes of all stripes) are worthy for no reason but that we exist. One way I'm showing solidarity is by donating to organizations that connect trans people to the help and resources they need. Trans Lifeline and Trans Youth Emergency Project are both trusted organizations within the trans community. They could use all our support.

Each of these books should be available for free online or at your local library. If you want to buy a gift for yourself or someone else, the links below go to my bookshop page. I'll be adding any money I make from sales to my family's donation to Trans Lifeline and Trans Youth Emergency Project.

Like previous years, my top 5 list includes a few honorable mentions. Robin Wall Kimmerer's The Serviceberry is a beautiful read about reciprocal relationships. Blue Delliquanti's Adversary is a graphic novel about transitioning during the covid pandemic. By Night in Chile by Roberto Bolaño is a weird-ass novel with no paragraph or chapter breaks. The Faggots and their Friends Between Revolutions by Larry Mitchell is finally back in print. This is queer history that still feels like boundless queer futurity. Here are my faves for 2025...

5. The Great Believers, by Rebecca Makkai

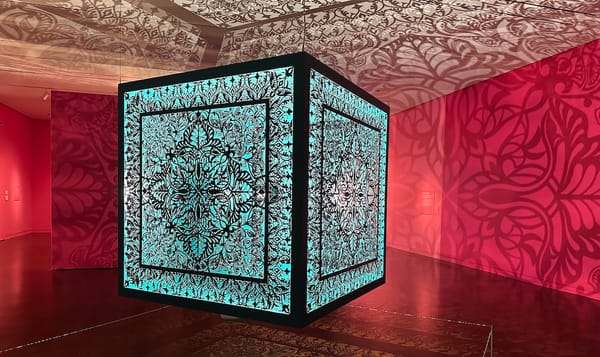

This novel is two intertwining stories about a group of friends who live in Chicago in the 1980s. Yale works at the art gallery at Northwestern University. He's introduced to Nora, a woman who holds a collection of rare and valuable paintings. Fiona is the sister of Yale's boyfriend Nico, who in the opening chapter has just died of AIDS. In Fiona's own story, set 30 years later, she is among the survivors of the AIDS crisis. Nora, part of the 1920s Paris arts scene with an art collection to prove it, is Fiona's great aunt. Yale's story goes beyond the acquisition of some career-making paintings. He and his friends are trying to find their way as their lives start to crumble to this terrible virus. Dan López of LARB writes, “what happens to the memories of all the lives cut down in their prime and, more urgent, who bears the burden and the privilege of being the memory-keeper matters a great deal.”

Who would have guessed that I would find a plot about donated paintings to be so thrilling? There is of course much more here than that. Reading books and novels about the AIDS crisis gives us a kind of cursed gift of hindsight. I ached alongside these characters. We know that HIV will doom many of them, and the impact of their deaths will ripple out from there. Some survived out of luck or caution, but too many didn't. Makkai's story tells us what happens, too, to some of the people in those ripples. How do they ever cope with so much loss? This was my first read of the year and it stuck with me all 12 months.

4. Rejection, by Tony Thulathimutte

This is a novel for the terminally online. The book is a collection of short stories that seem to have more in common than one might guess. Each story is about a person caught up in the modern world, stunted in some way they can't name. Craig is a self-described feminist who doesn't seem to think too much of women besides what they deny him. Alison tries to maintain the relationships in her life, ones she doesn't seem to like very much. Kant composes a very detailed request for an online sex worker. The stories collide and distort each other the deeper into the novel you go.

This is the funniest book I read all year. This is also the cringiest book I read all year. I was telling a friend about this book right after I read it. With patience, he listened to my summary before replying, "why would anyone want to read a book like that?" I don't know! For most of the book my face twisted in a painted rictus. These are not heartwarming characters! Thulathimutte draws characters that are compelling like a car crash is compelling. I related to characters in ways I didn't expect and wouldn't admit. But once I figured out they were all supposed to be like that I was able to settle in and enjoy the grotesque ride.

3. Sky Full of Elephants, by Cebo Campbell

One morning, every white person in america stops what they’re doing and walks into the nearest body of water. This is how Sky Full of Elephants begins. "Like a light turned off on a nightmare. They killed themselves. All of them. All at once." Charlie Brunton is a Black man and a professor at Howard University. When the event happened, he was locked in a prison where the guards all walked off. He would have starved if the families of other inmates hadn't broken in and freed everyone. The event transforms the entire country. People laugh and sing together, eat well, play and dance in the streets, and enjoy their lives. One year after it happens, Charlie gets a call from a daughter he never met and didn't think still existed. Sidney's mom, stepdad, and two half-brothers walked into the lake behind their mansion. She's calling Charlie, a man she resents, because she needs a ride from Wisconsin to Alabama to find the only other person in her family that's still alive.

This is the only sci-fi book in my top 5 this year (and only one of 2 all year!). The premise of the story had me hooked from the start. What would happen if the historic oppressors of this land all vanished? In what ways would we move on? What if the old life was what brought us real comfort? Would we repeat the same traumas in this new version of the world? Would we revisit those traumas on ourselves and each other? Or would we build something new? I loved the connections that the southern u.s. had to Haiti in this novel. As Sherring writes in her review, “the Haitian Revolution is what spurred the rest of the globe to fight for their independence from colonialism. Enslaved people in Haiti were the first people to fight for and be victorious against their oppressors. They gained their independence and suffered consequences that still reach centuries later.” Haiti offers a model for healing and a new way of doing things. This trailer (for a nonexistent movie or series) sells it better than I could.

2. Ducks, by Kate Beaton

Ducks is a graphic novel memoir by internet comic sensation Kate Beaton. The character Katie and her family are from the tiny town of Mabou in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. Katie is fresh from graduating college with an english degree and a lot of student loan debt. To pay it off, she does what so many young folks from Mabou do—she leaves. She gets a job working in a tool shed at one of Alberta's oil sands. The camp at the oil sands feels remote and lawless. The bitumen extraction industry is a male-dominated field. It's full of men who left families and loved ones behind to make money. Many of them are sensitive, kind, or gruff (or all three). Many objectify or prey on the young women who work alongside them. Everyone is lonely in the way that people get when they're months or years or miles away from home. Kate portrays Katie's experiences with and survival of sexual assault. When they happen, these events appear as solid black squares in sequence or even as a solid black page. Katie spends two years in this world growing up, trying to get by, and figuring out what to do with the rest of her life.

Hark! A Vagrant is a webcomic that I knew back in my AIM days. Recognizing the author drew me to this book but the matter-of-fact storytelling is what sold me on it. Each chapter begins with a set of little portraits for each of the characters in Katie's life at that time. Over time, Katie has a realization that the oil sands are not a neutral source of income. Natives and residents of the area suffer the clear environmental impacts of mining. A flock of birds dies in a wastewater pond they weren't supposed to land in. The company’s response is a PR apology and fixing a speaker that emits occasional noises to keep the birds away. The sands change people. They change men who come to see women as objects held at a distance. They change the women there for a job (like the men) but who are outnumbered and othered. And they change the community poisoned by the greed of folks who will never live there. Kate (and Katie) ponder how each person will carry away the choices they make in their lives. Katie worked there for 2 years, long enough to pay off her student loan debt. The local community, one just like Mabou, will deal with these sands for the rest of their lives.

1. Park Cruising, by Marcus McCann

Park cruising, in this context, means men having sex with men in discreet but public spaces. Toronto-based writer Marcus McCann writes about cruising as a human rights lawyer and activist. Cruising is a phenomenon that goes back centuries or even longer. But the canadian government brings its power to bear on men who find relationship in public places. McCann writes, “[C]ases from the last forty years rarely consider sexual expression valuable and worth protecting. Sex is only ever a problem. It is dangerous, harmful, risky. The law does not have language that accounts for park cruising as something that might contain elements of social good.” Cruising often happens in neglected spaces: the ratty-looking public restroom, the edge of a secluded parking lot, or a wooded area of a park. McCann describes the millions Toronto has spent to end the practice of cruising. They've tried police raids, stings, and crackdowns. They’ve devoted money to remake parks and put potential cruising sites more in the public eye. If the argument is that people shouldn't have to see it, why do we go through all this trouble to make it more visible? Why do we spend so much fighting an activity that almost nobody even notices? And could there be a public good to all kinds of people sharing public parks at different times of day? McCann navigates these questions through a series of legal issues he and other activists faced.

This was a fascinating, thought-provoking read. McCann's central argument is that sexual freedom and pleasure aren't frivolous. They're necessary aspects of everyone's bodily autonomy. He analyzes the history of moral codes and how they're used against all kinds of people. These are the same twisted morals that the state uses against trans kids and bathroom users. Even in Seattle, the Denny Blaine nude beach may shut down because it offends the neighbors. Sexual freedom rarely gets this kind of due in most of society. The essays and stories McCann tells kept me riveted throughout. It's the book I've thought about and talked about the most this year. I can't recommend this book enough.

we're still here

This year has not been easy for so many folks. I've struggled with the multi-pronged and multi-wave attacks on people I care about. But every day I'm heartened by the acts of defiance that bubble up too. I know we will outlive the architects of our attempted destruction.

The writer and philosopher Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò is also active on social media. One of my favorite bits of his is the rejoinder "we are going to win." He shares this mantra with every piece of good news he comes across. Even though our current situation may feel hopeless, we are going to win. Defeat is temporary if we get back up. Defeat is not the end. Like the folks in the books I loved this year, we may not have simple or easy lives forever. But we can always decide how we choose to live. We will not go quietly. We will stick together. We will fight back in every way we can. We won't settle for reform. We won't go back to what we had before. We are going to win.

We are going to win.