lessons from ‘born in flames’

this post is narrated! listen below…

this is a collaborative post: concepts and words by Jamie Martinez and josh martinez.

This is blog post number 100 on be the future! I’m so grateful that I can share it with my husband Jamie. During the pandemic they instilled in me a love of movies older than the 1990s. They are a lover of wordplay, super hilarious, a frequent collaborator, and the first person to read what I write each week. For this very special post we’re merging our interests into a really fantastic post. We hope you enjoy.

It’s ten years after the revolution in a world that feels like it’s both decades old and present day. Mayor Zubrinsky of New York City calls our country, “the first true socialist democracy the world has ever known.” America leans on exceptionalism to describe itself even in a socialist utopia. But in a country remade for race and gender equality, everything feels pretty much the same. So begins the independent science fiction film Born in Flames. Almost 40 years old, the themes and lessons we find in this movie are both prescient and commonplace.

We don’t know much about how the Socialist Democratic Cultural Revolution took place. We see a feminist perspective on the post-revolution society of the film. Discrimination on the basis of sex is still common. Women experience trouble advancing in the workplace, or even keeping their union jobs. The leaders we see in the film, from government to the news media to labor management, are all men. Newscasters still speak of women as inferior. Leaders deem women’s needs and issues not worth examining. The world is still more challenging for minorities, especially Black people. People who are poor or economically disadvantaged are still segregated from the wealthy. Government agents still sow drugs into these communities. These circumstances are no different to how things were in pre-revolutionary society.

The protagonist of the film is Adelaide Morris, a Black lesbian construction worker. Adelaide is a leader in the Women’s Army, a decentralized group of activists who fight for gender and racial equality. At the start of the movie, we find Adelaide and her associates trying to form alliances with others in the community. We meet two underground radio hosts: Honey at Phoenix Radio and Isabel at Radio Ragazza. Honey is a Black woman who broadcasts with an activist perspective. Honey also presents community journalism, such as covering an administrative support workers’ strike. Isabel is a white woman and a performance artist, poet, and punk musician. We only ever see Isabel interacting with a small group of colleagues, and rarely (if ever) in community.

Three journalists, all white women, write for the Socialist Youth Review. Their newspaper is state-run media that covers Adelaide and the Women’s Army in the film. The women are college educated and present a contrast with Honey, Isabel, and the Women’s Army. In one interview, they describe an incrementalist plan of action for women’s rights. They and women like them help set the country’s political agenda and goals. They also deny legitimacy to the community movements that oppose the socialist democracy. They claim these activists and their movements are “youthful” and not credible.

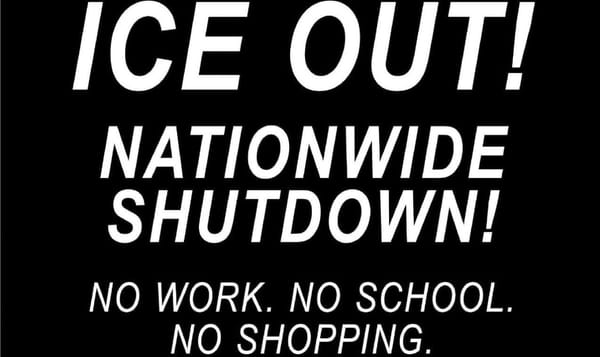

The Women’s Army’s tactics start out looking like the mutual aid groups of today. They organize childcare for working families and single mothers. They patrol the streets on bicycles, blowing whistles and interrupting an attempted rape. The police call them vigilantes, government agents track them, the media ridicules them. After some time, it becomes clear that the nonviolent activism of the Women’s Army isn’t enough to change the world so they can survive.

Adelaide’s colleague and mentor is Zella Wylie, a lawyer and activist. Zella is played by Florynce Kennedy who in our world is a lawyer, radical feminist, civil rights advocate, and activist. Zella tells Adelaide that “All oppressed people have a right to violence.” Zella later introduces Adelaide to a leader of the rebellion in Western Sahara. They agree to give the Women’s Army weapons if Adelaide comes to see their struggle firsthand. After Adelaide returns to New York, agents detain her at the airport. We later see her dead on the floor of a jail cell. TV news and the police are quick to declare that she died by suicide. Adelaide’s death is the shock that galvanizes Zella, Honey, Isabel, and the journalists. They finally join forces in true solidarity against an increasingly violent state.

This is one of Jamie’s favorite films, and it recently became one of mine as well. There are so many themes that resonate for us throughout this film. It warrants repeat viewings and group discussion. Born in Flames is available to stream on Kanopy (April 2024 update: it was recently added to the Criterion Channel too). For be the future, we will highlight three themes that felt most relevant to the activism and struggle of the present day.

maintenance of the status quo

The film begins with many leftist activists’ wildest dreams realized: a socialist utopia. But here, the police are still around, ineffective as ever. They don’t respond to assault in the streets but want to arrest the people who prevented it. The FBI is still around and following activists trying to survive. Countless moderates are still here to tell us that the status quo is the best you can hope for. In the movie Adelaide and other women lose their jobs to male heads of household. The government proposes wages for housework instead of what women are demanding through protest.

In this alternate reality, the only science fiction is the supposed political leanings of the powerful. They can claim their government is social democratic without having that mean anything. This may feel familiar in our representative democracy funded and dictated by billionaires and corporations. But the point of the film is not cynical in nature. It’s not saying that all governments, no matter who controls them, inflict the same harm on society. Its message is that any form of power is weak if it refuses to consider the needs of all people. No matter its hold on society, it’s only a matter of time before it will crumble and fail.

power is exclusion

In the film, we see a few pitch meetings for the Socialist Youth Review. The white women we see discussing stories initially dismiss Adelaide’s cause as unserious. We see them decide what is fit to print and what is too dangerous to write. After Adelaide’s murder, they look into the coverup and blame the state in their article. Only then do we see their editor, a white man, who tries to intimidate them out of publishing the story. When they publish it anyway, he fires them. In Born in Flames, power is exclusion. The journalists are free to exclude the interests and common cause of Black women. They later suffer their own exclusion by the white men who are the real holders of power.

Honey tells her radio audience that, “every woman under attack has a right to defend herself.” You could replace “woman” with any identity and it would still ring true. There would still be considerable opposition from people in positions of power. This is no different than the real United States of the 21st century. The defund movement and Indigenous water protectors are two current examples. These activist communities face considerable opposition from both conservative and liberal power structures. Incrementalism and moderation continue to downplay the needs of the oppressed. Systems continue to uplift the desires of the powerful white, rich, and cis men. The film demands that we examine the lack of engagement with systems of change.

gatekeeping the revolution

Gatekeeping a movement can dictate how it’s presented in mainstream media and culture. People in power decided that filling desk space in office buildings is more important than workers distancing themselves in a pandemic. Tech companies will post messages in support of Black Lives Matter to social media while they sell tracking software to police departments. People with wealth will choose to market and commercialize anticapitalist and abolitionist rhetoric to devalue its meaning.

Even as they fight for justice, voices throughout the film suggest society has done too much for people in need. At the end of the film, another male newscaster asks, “Have we gone too far?” He warns that after ten years of socialist democracy, society has become a welfare state and only austerity is the answer. The society we’ve seen gives preferential treatment to men. It paternalizes and belittles women who want equal pay for equal work. The President hears that women need jobs so he offers to pay them to raise kids at home. He’s willing to meet their needs only through the lens of what society wants them to have. That, the movie makes clear, is not progress.

Born in Flames is sometimes described as a dystopia, but the people who live in the film never feel defeated. Their world and progress may feel like such a dream compared to the world we live in. Born in Flames teaches us that even when we achieve our wildest dreams, we will still have work to do. Here are three lessons we’ve taken from the film.

unity is not the same as solidarity

Throughout the film, the oppressive state calls for unity again and again. Calling any contrary opinion divisive is a neat trick to use against your enemies. Unity in political power is usually dictated by power brokers who do not intend to relinquish control. In our United States you see this magnified in election years when dissent against either major party is seen as a threat to freedom itself.

The film contrasts “unity” from the perspective of the party to the solidarity the activists have at the end of the movie. Zella provides guidance to Adelaide and to the Women’s Army in one of the most memorable parts of the film. She says,

They always talk about unity. We need unity… But, I always say, if you were the army and the school and the head of the health institutions and the head of the government, which would you – and all of you had guns – which would you rather see come through the door? One lion, unified, or 500 mice? And my answer is: 500 mice can do a lot of damage and disruption.

Her revolutionary message is that slight differences in ideology can still work together. A horde of mice is still united, but each one’s movements are nimble and independent of other mice. The people with guns may shoot a mouse or two, but they’ll never get them all. The analogy also invites us to dive deeper into what unity really means.

“Unity” can mean we have a common cause but our causes won’t completely align. We agree on some things and are free to disagree on other things. “Solidarity” is durable and more valuable in a struggle. Solidarity means that I accept your causes as my own, and you accept my causes as yours. When we’re talking about an individual’s needs, unity may get me some of what I need but no more. Solidarity gives me the freedom to dissent and be heard without either of us losing our agency.

revolutions are permanent

At the start of the movie, advocates for socialist democracy are long past their victory. Yet the problems of the old world are not yet resolved. White men are still in charge in almost every area. America treats men’s needs as sacrosanct while women’s needs are negotiable. They hold power throughout the film, never at risk of losing it. The film’s most notable man of color is Mayor Zubrinsky. Though he is Black, he still upholds the white supremacist paternal culture that elected him.

In our world under covid, anti-vaccine sentiment can be as durable as a religion. But people who feel that way would likely still be here if the revolution took place tomorrow. How do you change their minds? How do you unfix their deeply-held beliefs? How do you do that while they’re trying to unfix yours?

When we achieve our goals, our wildest dreams, it’s okay to rest as long as we get back up again. There will always be people who our plans forget. There will always be people who fight tooth and nail against our goals. The remedies of today will grow stale or outdated. It’s up to us to hold onto our solidarity with other humans, receive their needs, and bend towards justice.

performance is not as strong as action

Isabel initially refuses to join the Women’s Army because their collective activism is not strong or violent enough. This is despite the fact that Isabel is never seen doing any form of non-performative activism in the entire film. In the same way, the “socialist” party in the movie acts like the Democratic party of our reality. Incrementalism and reactionary laws are the only way they know how to govern. They are not an abolitionist movement. Even in a country whose goal is to remedy injustice, they can still perpetuate that injustice. The party can say they are the first true socialist democracy, but that alone won’t make it true.

Instead, we see only the Women’s Army meeting the needs of their neighbors through mutual aid. What might a decentralized collective of BIPOC women do with the full autonomy and power over their own futures? If you hold a position of power, no matter what it is, you have an obligation to serve more than yourself. We live in a time of great need. Do our actions match our statements?

Born in Flames is a thought-provoking film. After 40 years, its themes resonate with our present day. Its lessons help us give thought to what we want our future to be.