why do people with power still work on the margins?

I got into management for reasons that people rarely say out loud. I have seen many examples of people abusing or neglecting the power their system gave them. I wanted to do it better. The pace of change has always frustrated me: who are we waiting for? How do we get them to speed up? I spent so long watching others use their power that I daydream about all the ways I would use it.

being marginalized but in power

It comes up a lot in the government and non-profit arenas where I’ve worked. In public health, people run by the adage, “when we do our jobs well, you don’t even notice us.” Unfortunately, the sober, behind-the-scenes government worker is an antiquated notion. This self-defeating view is like an early-release Imposter Syndrome. We are experts in our fields, but nobody will take us seriously. We can do, but can we lead?

In our reality, people who are afraid to rock the boat are minimally rewarded. Nowadays, governments don’t fund the things people don’t care about. Police departments are a great example of this. They and their unions proclaim in a screech the dire consequences if we cut their budgets. Amid weeks of police brutality, the Seattle city council pledged to cut SPD’s budget by 50%. The police and other city actors made their displeasure known to anyone who would listen. When the dust settled, the council overrode a mayoral veto to affirm a measly $3M cut to the current year’s $409M budget. Most of this cut won’t even impact the department: it’s too late to lay off staff before this budget year ends. They will have to start the negotiations all over in just a few weeks. Meanwhile for decades, austerity budgets have slashed all the parts of government that don’t kill people.

So why do we do it? Why are people with power so afraid of using it?

at the mercy of themselves

Most people in non-profits think of themselves as progressive. Or at least, progressive enough. It’s true for me, too! I worry all the time about whether my “innovations” are “radical” enough for the original name of my blog (radical innovations). So we take this mindset and think that things are moving enough. We’re fighting the good fight, but going further would be going too far.

But what if we never fight for as much as people really need? What if the space that I occupy is taking up sufficient oxygen to snuff out the efforts of others? What if I’m the Pete Buttigieg of the non-profit world? What if our progressive values are just milquetoast centrism? What if we’re stifling actual good ideas with our own narrow-minded approach? (side note: one of Buttigieg’s campaign slogans is “win the era,” so thanks Pete for making me wonder if "be the future" comes across as just as bland).

what’s worked for me

When I’m at the mercy of myself, I tap into emotion. I do enough doomscrolling to remember that things are not getting better on their own. I get angry enough with the system to want to do something about it. And then I remember that my position of power means that I can!

at the mercy of peers

Feeling out of step with peers can be an awkward experience. It’s easy to worry about what people will think about us, even when we’re fighting for the same things. It’s hard to have hard conversations, especially if their answer might be “no.” It can feel isolating, but gentle conversation shouldn’t make someone a pariah.

what’s worked for me

I try to mix things up. I keep myself educated by reading a lot. I write and sharpen my arguments. And I dare myself to try selling my audacious visions. It doesn’t always work, but people know where I stand. They know I won’t be happy upholding a harmful status quo.

at the mercy of the powerful

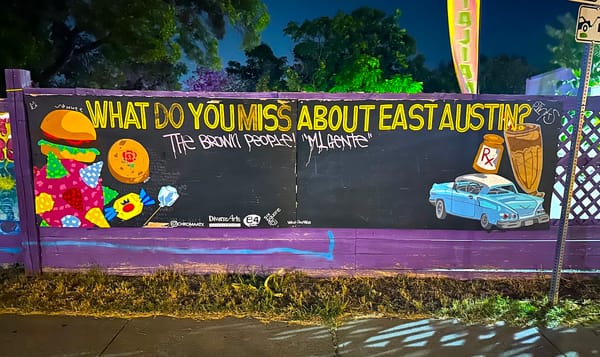

I’ve spent most of my life working on the money-losing side of businesses. This includes a stint selling gelato in Austin, where I ate almost as much as I sold. I know that funding has to come from somewhere, whether it’s taxpayers, donors, or funders. But it could also include peers in power, or a CEO, or the person taking notes when I complain about capitalism near an Echo.

what’s worked for me

Those people are all human. If we go into conversations expecting “no,” then we dare our listeners to meet our expectations. I’ve found that most of the time, people are afraid even to ask. I’ve never met a funder who said, “this was such a terrible idea that I am going to revoke all my funding to you, for all time.” But even if they do say no, that’s an opportunity to find out why. It’s a chance to engage them, educate them, and invite them into a solution.

how else can we break the cycle?

We can find a new job or a new perspective on the old one. We can ask more questions and listen to the answers. We can take more risks and learn from those that don’t pay off. We can keep fighting to do things in different ways. Those ways won’t be perfect. We can’t give up. We must take the wins and the losses and keep trying.

The core of each of the categories above is fear. Fear of failure. Fear of the unknown. Fear of never being good enough. Like any source of fear, we can’t run from it. The people I’m fighting for are fighting alongside me. They’ve been fighting longer and harder than me, and their fight is personal. I’ve taken their fight on as my fight. I’m not going to give up.