asking for ID in the surveillance age

The vast majority of us have internalized data collection as a fact of life. It feels natural, doesn’t it? I show my ID to get into a concert (those were the days!). The websites I browse collect huge amounts of data from me. Security cameras dot my periphery in most public spaces. I’m sure that my credit card data is floating around. But when I go to the grocery store to buy a loaf of bread, nobody asks me for my ID. If I choose, I can pay cash, and nobody will even have to know how much bread I eat (it’s a lot ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ ).

But my experience might be different if I can’t afford that bread. My experience accessing a food bank, for instance, might depend on where I live, what I look like, the vehicle that I use to travel there. It may depend on how many children I have, and how many children I look like I have. It would depend on how one or two gatekeepers of donated food felt about me.

If they believe me, I pass. If they don’t, I starve.

A food bank is the last place in the world to restrict access to food. It is an abuse of power to ask someone for ID, for even a piece of mail, to prove they deserve to receive food.

who might not want to show their ID?

First think about why asking for ID or a piece of mail might be an imposition to someone. Here are a few to get started:

- People who are trans or non-binary. Their ID might not match their gender identity. It might list a name or photo that does not represent them.

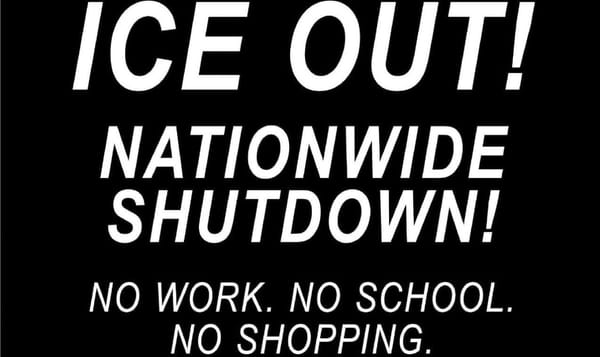

- People who live in the US outside the legal immigration system.

- People who feel stigma or shame from having to use a food bank.

- People who are afraid of identity theft.

- Children who are seeking food for themselves or their family.

- People who forgot their ID that day, or left it on the bus, or don’t have one.

Everyone on this list, and even people I didn’t describe, still deserve food! Everyone does. If this is someone’s first time at that food bank, a demand for ID may cause them to never come back. How can that person feed their family now? Where else should they turn? Fewer people accessing food banks can mislead a community about the true level of need in their area. It means more people will go hungry in a nation where there is plenty of food.

what’s good for the goose has nothing to do with the gander

Some people defend their decision to ask for identification or a piece of mail. They say something like, “I wouldn’t ask anyone anything that I wouldn’t be willing to give myself.” But their privilege is that they’re not the ones asking for food. They’re not in the same situation. In this case, they are the holders of power. They are the gatekeepers of food donated to help people in need.

A food bank policy, or a personal decision (or a hunch or feeling), to request ID means the person at the door is now a gatekeeper to food. It means they get to decide who can eat and who cannot. When we leave decisions up to humans, or even when humans write the policies, we know they bring their own biases into the decisions they make. If they don’t believe a person’s story, or don’t believe that they really have four kids at home, they have the power to ask that person to prove it. And what happens if that person can’t? The cashier at the grocery store doesn’t ask me how many children are going to eat the bread I buy. I don’t have to bring a handful of birth certificates or medical records to buy the sheer volume of bread that I eat.

Access to food should not be subjective. The people who ask for ID should consider the real risks of requiring this information. Not the risks to themselves, but the risk that others perceive for themselves.

Some gatekeepers interpret an ID as an indicator of legitimacy. They might say ID is no problem for people with “nothing to hide.” But nothing worth hiding should prevent you from being able to eat. It’s easy to forget the amount of time it takes a person to get an ID. It’s easy to forget that every food bank’s rules are different. If you get them wrong you have to come back with the right documents. If it’s a two hour bus ride round trip from the food bank, it might take days to come back. It’s easy to forget that if I am worried about my safety, or my family’s safety, giving a stranger my ID is a risk. It’s easy to forget that if the gatekeeper doesn’t like me, or doesn’t trust me, thinks I’m an outsider, I am the one who suffers.

the good could be gooder

The programs my organization operates are all self-declare, no-proof programs. A self-declare program means people give us the information themselves. We still collect some data, but do not require personally-identifying information in order to receive food. A no-proof program means we don’t ask anyone to prove what they tell us.

The most common federal food assistance program asks us to collect the name and address of the person receiving food. It also asks them to affirm that their household income is below 400% of the federal poverty line. We ask them to name the number of people in their household. this helps represent the accurate number of people using these services. We are not allowed to verify this information. And why should we need to?

But we don’t even have to do it this way. The first rule of storing data is simple: you can’t turn over what you don’t collect. If you collect no personal information, no one can force you to give it to them. Nobody can steal it from you. The strongest decryption program can’t unlock what doesn’t exist.

Funders that restrict food to a specific population or territory are part of the problem. We need to remove these restrictions from all programs that perform a public service like food assistance.

We have to end the needless hoops we put up for people in need. It’s scary enough to go without food, to be in a situation where things are going so wrong you have nothing to eat. It’s scary to feel helpless, but it’s even worse to have an empty stomach too.

We in the non-profit world should be serving the public good, not creating more barriers for them.